Trees are battling the climate crisis, pests and diseases throughout the UK. Richard Cobb, Local Partnership Advisor for the South East and London, shares what we can learn from recent research in London.

Trees are battling the climate crisis, pests and diseases throughout the UK. Richard Cobb, Local Partnership Advisor for the South East and London, shares what we can learn from recent research in London.

Trees and woodlands are one of our most effective tools for tackling the climate and nature crisis and deliver many other benefits [1], but they’re at huge risk from climate change and pests and diseases.

The London Urban Forest Resilience Project has been investigating the challenge. Our new report [2] shows what policy makers, funders, local authorities and tree professionals can do – in London and beyond.

I’ll share some of the key findings to show how the impacts of climate change, pests and diseases can be assessed and managed. The project has made it clear that we need to do more to safeguard the urban trees we have and the new ones that many are working hard to establish, and Local Authorities will need support and resource to manage them.

Why London?

London boasts a broad diversity of tree and woodland types that inform an integral part of the city’s landscape. They weave their way through and around the capital from understated oases among dense urban living to the vast and prestigious.

London’s urban forest consists of 8 million trees; in royal and public parks, along streets, rivers, road, canals and railway, copses and woodlands from brand-new to ancient, hedgerows, gardens and more. In other words, a microcosm for much of the variety that we find across England.

The infographic above represents where London's trees are:

- Along transport routes and waterways.

- Parks, nature reserves, informal green spaces.

- Street trees.

- Private gardens.

- Hedges.

- Urban green spaces – housing estates, schools, hospitals.

- Urban woodlands including ancient.

- Green belt.

The report analysed the vulnerability of London’s top 10 most common street trees, which accounts for 35% of the capital’s overall street tree population. While London- and street-tree focused, this report provides lessons and a robust model that can be adapted to other settings, and to all other component parts of a local tree population.

The threat of climate change to London's trees

London and the surrounding areas in the south of England are anticipated to be among the first and most severely affected by climate change (Forest Research). As highlighted in the London Climate Resilience Review, the impacts of climate change are already being felt and will only become more prevalent in the future with more droughts, extreme wind, wildfires and expanding pests and diseases.

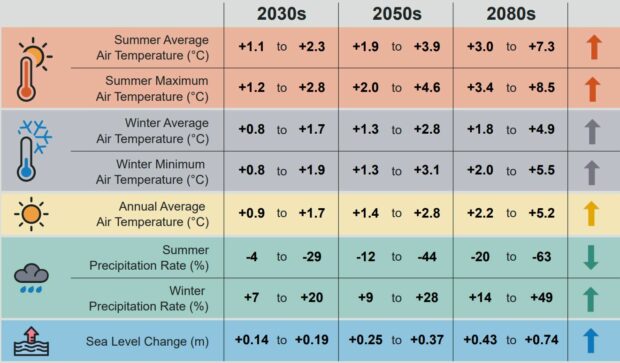

A snapshot of some of the key anticipated changes is provided below (CHELSA):

We rated the risk that threats such as drought, flooding and wind present to London’s top 10 most common street tree species, using multiple sources. This assessment considered two climate scenarios: one where CO2 emissions are limited (RPC 4.5) versus a business-as-usual scenario (RPC 8).

Our findings are sobering:

- by 2050, under a climate projection where CO2 emissions are limited (RPC 4.5), up to 9 of the 10 species assessed may be approaching the mean temperature limit they can tolerate. These trees would experience greater stress, be more vulnerable to pests and diseases and would require more management to survive

- by 2080, under a business-as-usual scenario, for up to 8 of the species assessed there is limited evidence to support that the species in question can survive

- 4 out of 10 of the most common street tree species in London are known to have low tolerance for drought, and 6 out of 10 are known to have low tolerance for flooding (soil waterlogging), which would further compound tree stress and vulnerability

The threat of pests and diseases to London's trees

Pests and diseases are also a serious threat. This is not a new challenge, but its impact is compounded with the added stress changing climate will impose onto trees and the likely increase of new pests and diseases able to thrive in the UK. We only have to look at the likes of ash dieback to see the devastating impact that just one disease can have.

The Forestry Commission, Forest Research, and the wider sector have been working hard on these challenges for a long time including proactive efforts to monitor, manage and prevent the spread of pests including those relevant to London such as Ash dieback, Ips typographus and oak processionary moth.

The report shows that collectively the top 10 most common street tree species in the capital are vulnerable to 51 pests and diseases deemed to represent a ‘medium’ or a ‘high risk’ in the UK Plant Health Register. Four of these are already present in London while seven more are known to be present elsewhere in the UK.

Even with mitigation measures in place, about 15 of these pests and diseases would continue to represent ‘medium’ or ‘high’ risks.

Between the time of producing the report and releasing it, the plane lace bug tree pest has been identified on a number of London plane trees in central London, which we are investigating. This demonstrates how important it is to proactively anticipate and monitor threats as they emerge.

It’s clear that tree managers will be under greater pressure in the future to dedicate more resources to pest and diseases management – either through preventative or remedial action. Prevention should pay for itself in the long run, but these are challenging economic times.

Actions to improve resilience

The report fulfils two commitments in the London Urban Forest Plan (LUFP) [3]. First, to assess the threats of pests and diseases and climate change on London’s urban forest. And second, to develop a set of principles for improving resilience to these threats.

We’ve outlined best practice guidance and practical actions to enhance urban forest resilience in the report. This was informed by an extensive literature review, national and local data, insights from local stakeholder workshops and expert peer review.

To help support effective local and landscape-scale action, the report provides some practical recommendations on key good practices and principles to guide this journey including:

- manage at landscape-scale – threats of climate and pests and diseases don’t conform to political boundaries. Pool efforts, knowledge and resources to maximise effectiveness

- establish your baseline - use the current and predicted local climate to inform suitable species for now and in the future

- establish and prioritise existing and potential pests and diseases - that pose the greatest risk for the trees you have, and understand their dynamics

- ‘spread your bets’ - plant a diverse range of species to support biodiversity and reduce the risk of loss from a single threat. Agree the species list up-front based on local knowledge, experience and inspections, and share this far and wide

- prioritise and monitor tree health – healthier trees are far more resistant to threats than stressed ones; prioritise the ones identified as highest risk

- ‘you can’t manage what you don’t measure’ - assess existing tree stock and collect data in a consistent way i.e., species, age, classes, condition

- focus on tree establishment, not just planting - prioritise quality, not just quantity. We need the right trees in the right places. Start small, test, learn from experience and repeat

- seek cross-departmental funding and share your objectives with other teams, partners and communities – they can help you deliver and make best use of the resource you have. Understand the priorities of other teams and stakeholders and promote trees as assets

- specify robust biosecurity throughout procurement - to safeguard tree health and prevent the spread of pests and diseases. It’s well worth the investment

- embrace the inspiring power of local people – it’s hard to overstate the value that local champions can humbly provide to local trees; carrying out essential maintenance, planting, and monitoring on the ground. Investing some time to empower and inspire more people within the community and upskill them in what to look out for, when and how to report can turn curious locals into a powerhouse of citizen science

Change will take time

Establishing and expanding the next generation of trees is crucial but they will take time to deliver the same benefits that mature trees already provide, which also represent the vast majority of the total treescape.

The message is clear – more attention and support is needed for tree management if the long-term value of these assets is to be secured for more sustainable, climate-resilient and healthier places to live and work [1].

Read the full guidance, methodology used, resources and actions outlined in the resilience report in the London Urban Forest Resource Hub.

References

[1] Research has been carried out to try and illustrate how much value the ‘ecosystem services’ trees provide in monetary terms; £133 million of value for London every year (Greater London Authority, 2018), £3.8 billion for individual trees outside woodlands in the UK (Forest Research, 2022), an asset value of £382 billion for UK woodlands and a total annual value of £10 billion (ONS, 2024).

[2] The full report can be found in the London Urban Forest Resource Hub. Treeconomics were contracted by the Forestry Commission, supported by Mayor of London and London Tree Officers Association, to carry out the project and author this report which involved extensive literature review, stakeholder engagement and expert peer review (see Acknowledgements and Consultation sections in the report).

[3] London Urban Forest Plan (2020).

[4] Met Office (2022) UK Climate Resilience: London City Pack.