Emily Robinson, Content Officer at Forestry Commission, shares what amphibians are doing in woodlands throughout the summer and discusses various woodland management actions you can take to support them.

Emily Robinson, Content Officer at Forestry Commission, shares what amphibians are doing in woodlands throughout the summer and discusses various woodland management actions you can take to support them.

When most people think of amphibians, they picture frogs sitting on lily pads or newts gliding through garden ponds. But if you look closely, you can catch glimpses of common toads and frogs, as well as smooth, great crested and palmate newts in our woodlands.

We usually spot them during their brief aquatic breeding season, but come June, our amphibians are moving to a life on land hidden among fallen leaves, rotting logs and woodland shadows.

It starts with a humble woodland pond

All seven of Britain's native amphibian species return to water to breed. Their jelly-like eggs survive only when submerged and once hatched, the tadpoles rely on delicate gills to extract oxygen from water. Through spring's lengthening days, eggs and tadpoles undergo a metamorphosis – trading gills for lungs and tail for limbs as they prepare for life on land.

Woodland ponds serve as far more than amphibian nurseries; they anchor entire woodland ecosystems. During parched summer months when streams run low, they become vital oasis points providing crucial drinking water for mammals, birds and countless smaller creatures. They also become bustling insect breeding grounds, supporting midges, mosquitoes and aquatic invertebrates that feed woodland bats, spiders and birds.

The journey beyond the pond

This aquatic beginning sets the stage for a surprisingly terrestrial (land-based) life, as they begin their journey by foot. Each summer, thousands of tiny frogs, toads and newts emerge from woodland ponds and carpet our forest paths.

These first weeks on land represent the highest mortality period in their lives, as the young face predation and desiccation (drying out, due to their permeable skin) in the pursuit of finding a suitable home. Woodlands become their sanctuary – an ideal habitat as they are often humid and damp with an abundance of insects, ample shelter from predators and reprieve from the heat.

During active months, they shelter under fallen logs, in leaf litter and within rock crevices, emerging on damp nights to hunt. When winter approaches, they enter a state called brumation – like hibernation but specific to amphibians and reptiles – tucking themselves away in log piles, beneath stone walls, in compost heaps or underground burrows.

Great crested newts may travel over a kilometre from the ponds they emerged from, establishing territories in completely different woodland areas. Common toads can travel even further, migrating up to 3.6 kilometres1 before returning to breed in the exact ponds where they were born. Common toads have even been found in trees, making use of tree cavities and dormouse nest boxes2!

Why amphibians are integral to our woodlands

Amphibians have quite the appetite for woodland delicacies and their place in the food chain reveals how valuable they are to woodland ecology. They consume vast quantities of slugs, insects, worms and spiders, providing natural pest control services that benefit woodland health. Frogs and toads can eat around 10,000 insects in a growing season. At the same time, they are prey for birds, mammals and reptiles – making them an essential part of woodland food webs.

Beyond their ecological role, amphibians serve as environmental indicators, meaning they can be used by ecologists to determine the quality of an ecosystem (particularly in terms of pollution). Their permeable skin and dependence on external temperatures to guide their behaviours make them extremely vulnerable to environmental changes and climate fluctuations. When amphibian populations begin struggling, it often signals that other species in the ecosystem are facing similar challenges, making them invaluable early warning systems.

Helping amphibians to thrive in our woods

Understanding amphibians as terrestrial animals transforms how we approach their conservation. Supporting them requires thinking beyond pond creation to encompass their entire lifecycle needs – a shift that benefits not just amphibians but enhances habitat for countless other woodland species.

Retaining fallen deadwood within forest stands provides crucial shelter habitat. Log piles, stone heaps and deep leaf litter layers offer hibernation sites and summer shelter. Avoiding pesticides and chemical treatments in woodland areas protects both amphibians and their prey.

Creating and maintaining woodland rides, clearings and edge habitats offers important transitional zones that support diverse plant communities and varied insect populations. These areas provide rich hunting grounds for amphibians, while the contrast between dense woodland and open spaces creates habitat mosaics that support the highest levels of biodiversity.

While amphibians spend most of their lives on land, breeding ponds remain essential. Incorporating ponds in the early stages of woodland design can avoid future conflict between species interest. For example, removing developing scrub in a maturing woodland to create a pond could potentially have negative impacts on other species such as dormice, bats and birds. It is therefore advised that opportunities for pond creation are explored as part of the woodland creation process.

The key for a thriving amphibian population is creating and maintaining pond networks rather than isolated water bodies. Multiple small ponds scattered across a landscape prove more resilient than single large ones, providing backup options when some dry up, become polluted or experience other disturbances.

Protecting amphibians during forestry operations

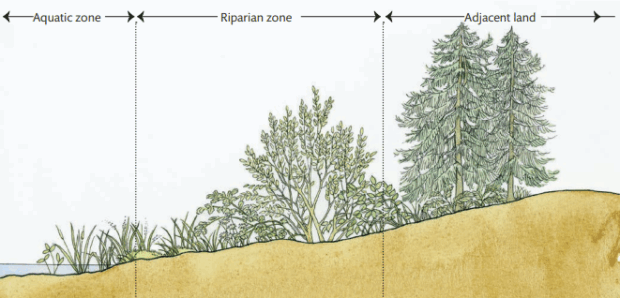

Terrestrial habitats, while more difficult to identify than aquatic habitat, typically extend throughout woodland areas adjacent to breeding ponds (see image above). Care must be taken when using machinery within sight of a pond or waterbody, as outlined by the UK Forestry Standard.

For ponds that may support great crested newts, it is essential to follow the European Protected Species (EPS) protocol and the European Protected Species in Woodlands workbook. Great crested newts are protected in the UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and are a European protected species under the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017.

Implementing appropriate precautionary measures during operations such as buffering water bodies can significantly reduce the risk of inadvertent disturbance or harm to this protected species and other amphibians. For more information, there is available guidance on managing woodlands with great crested newts.

Amphibians to look out for in early summer

Understanding the terrestrial habits of amphibians opens new opportunities to observe them in woodland environments. Next time you walk through a woodland and find yourself near a pond, take a closer look at the ground.

This is the time of year when frogs and toads are emerging from their aquatic birthplace – and they'll be no bigger than your fingernail! These tiny animals are embarking on the journey of a lifetime, trading their aquatic beginnings for the hidden world of woodland floors.

Find out more about how trees and woodland benefit nature on our GOV.UK collection page.

Images are sourced from Pixabay, with the exception of the smooth newt image (Wikimedia Commons) and the UKFS diagram (Crown copyright).