Jessica Turner, National Historic Environment Advisor at the Forestry Commission, explores how pivotal periods in history led to the evolution of the tools our ancestors used to shape our wooded landscape.

Jessica Turner, National Historic Environment Advisor at the Forestry Commission, explores how pivotal periods in history led to the evolution of the tools our ancestors used to shape our wooded landscape.

As the names of our prehistory suggest: the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age were all responsible for the evolution of tools.

While there is archaeological evidence of Palaeolithic (early Stone Age, from 'palaeo' – old and 'lithic' – stone) activity in England, it is rare and most of the evidence of the Stone Age dates from the late Mesolithic (from the Greek 'meso' – middle). This was around 10,000 years ago, when the ice sheet had retreated after the last Ice Age, and trees, plants and people slowly began to recolonise the land.

Birch was the first pioneer tree species, followed by pine and then hazel, elm, oak and alder. At the same time hunter-gatherers were refining their use of stone tools and specifically axes. These tools enabled them to cut small trees, creating clear glades (spaces) to attract wild animals to graze, which made hunting easier. The cut trees were suitably used for shelter, firewood or tools.

And so began our personal connection with woodlands. People started to manage wild woodlands which resulted in a mosaic of habitats including varied forest tree ages and structures, that could support greater biodiversity.

How our leafy landscape changed

During the Neolithic (‘neo’ meaning new) period, around 4000 to 2000 BCE, the population grew and the climate improved. This resulted in a huge societal shift from transient hunter-gatherers to permanent settlers, agriculture and animal domestication.

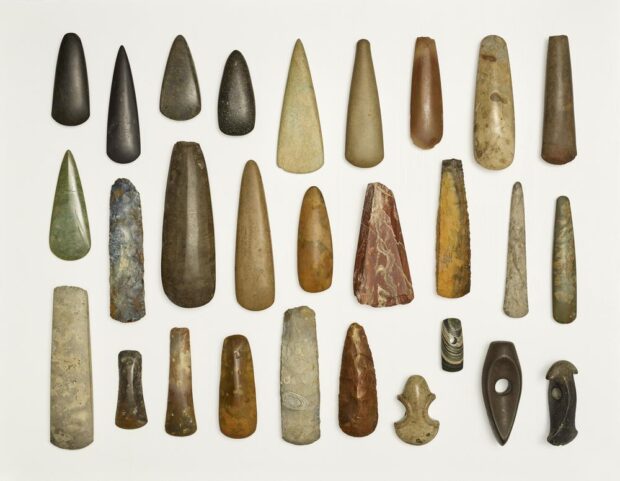

Advancements in axe technology enabled this societal change, as better stone axes and adzes (a tool similar to an axe with an arched blade used for cutting and shaping wood) with improved, fixed handles meant people could fell and process larger trees. Therefore, more substantial timber was available, which could be used to build permanent homes, fences and stockades (wooden barriers).

This permanence in the landscape meant people could make real landscape change. This came in the form of building the first large ritual stone monuments and people actively managing woodlands. As any good woodland craftsperson knows, the most useful age to coppice (periodically cutting specific trees down to near ground level to promote regrowth) to produce sticks, handles, wattle (a material used for making fences) and panels is around 7 to 10 years. By the late Neolithic/early Bronze Age we had the permanence and axe technology to actively manage woodlands on rotation – a sustainable cycle of cutting trees to enable regrowth.

Magical metals of the Bronze Age

Imagine how people must have admired axe makers throughout the Stone Age. Then in the Bronze Age (around 2000 to 800 BCE), smelting copper and tin alloy to create bronze was seen as pure alchemy.

There is evidence of polished Stone Age axes being symbols of power, prestige and social value. But the magical qualities of the shiny, bright metal axe meant that their association with ritual and ceremony became as important as any purposeful achievement.

The angles of an axe, or more precisely, the lack of angles – drove the technological revolution of the Bronze Axe. The flat, widened blade enabled more efficient tree felling, which meant people could cut down trees of greater age. The metal adze enabled more sophisticated house-building techniques. The axe helped our ancestors to start to take control of the environment.

Increased food production and population increase go hand in hand, and the Bronze Age witnessed large-scale wildwood clearance and the creation of field systems.

Forever shaping our landscape

The large-scale woodland clearance continued into the Iron Age (around 800 BCE to 43 CE), which relates to a period of iron tools and weapons. Our climate declined, with a shift from warmer and drier conditions to a cooler and wetter climate. This made it hard to maintain much of the higher altitude farming that started in the Bronze Age, and the higher plains turned into moorlands. Demand and technology started to outpace nature.

Another consequence of Iron Age technological advancements and the changing climate was that resources became more precious, and people needed to defend their homes and land. Thus, for the first time, our ancestors made weapons of war on a large scale.

However, the humble axe remains the perfect multi-functional tool, and its evolution has shaped our landscape. Testimony to its legacy is that its form and function is largely unchanged since the Iron Age. It is also charming to think that the next time you look at a woodland management plan, that 10-year rotation is deeply rooted in our past.

For more information on woodland management, read Woodland Resilience Advisor Chris Watson's blog Why woodland management matters.