Sonia Reveley has been Woodland Specialist at Bat Conservation Trust since 2017, working to raise awareness of bats and secure the future of bats and the woodlands they rely on. Here, Sonia explains more about UK bats, the challenges they face, and how woodland owners and managers can help.

Sonia Reveley has been Woodland Specialist at Bat Conservation Trust since 2017, working to raise awareness of bats and secure the future of bats and the woodlands they rely on. Here, Sonia explains more about UK bats, the challenges they face, and how woodland owners and managers can help.

Bats account for more than a quarter of mammal species in the UK and are the top nocturnal predators of flying insects. Most of the 18 bat species found in the UK evolved to use trees as roosts, while many also forage in woodland. Depending on their preference, as habitat choice can be species-specific, they search for their prey in woodland, along woodland edges and waterways.

Each bat species favours different insect prey. For instance, the common pipistrelle prefers midges, while the brown long-eared bat feeds on moths and beetles.

Woodland and trees are also important commuting wildlife corridors for bats, enabling them to move from their roosting sites to their foraging areas. Linear features such as woodland edges, hedgerows and tree-lined waterbodies provide much needed cover and protection from predators, and three-dimensional structures for echolocation calls to bounce off, acting as important navigational landmarks.

The importance of trees to bats is further emphasised by their choice of shelter. Most bats prefer to roost in tree features like cracks, crevices and holes, when available, either high in the canopy when rearing their young or low and deep in hollows when hibernating. Some bats are woodland specialists - habitat-specific species that have a strong preference for roosting in trees and foraging in woodland.

Changes in bat populations

The latest scientific findings from the 11 bat species monitored through the National Bat Monitoring Programme, a world-leading citizen science programme, show that at a national scale, they are either stable or have increased overall since the baseline year of monitoring in 1999.

However, this only reflects recent changes because bat populations have suffered significant historical declines since the start of the 20th century. In addition, we do not have trends for the other 7 UK species because they’re either hard to monitor or rare. It’s these species that are particularly vulnerable to habitat loss. A recent study looking at historic declines showed that one of our woodland specialist species, the barbastelle, declined by 99% over several hundred years, beginning 500 years ago, likely triggered by the loss of woodland.

Despite the good news that some species are stabilising, bats continue to face challenges. They have specific roost requirements, they cannot move very fast when hibernating or when young are present, they rest in their roosts during the day when most works are carried out and many have a close association with structures and habitats that humans want to change in some way. This means they are vulnerable to a suite of pressures including:

- landscape changes due to habitat loss and the loss of food prey from agricultural intensification, plus the use of pesticides and chemicals that bats are particularly susceptible to

- unsympathetic building and development work that can affect roost sites, key foraging areas and break up commuting routes

- light pollution that can make commuting and foraging routes inaccessible, delay emergence from roosts, and change bats’ feeding behaviour

In addition, new challenges are emerging, from climate change to wind turbines, as well as potential changes to regulations, policies and wildlife laws that may impact legal protection.

Managing your woodland for bats

To help bats, landowners can ensure their woodland supports a mosaic of different habitat features. This will also help a range of other species.

Retain trees (especially mature broadleaf trees) with features like hollows, snags, crevices and loose lifted bark including standing dead wood. This will provide a continuity of suitable tree roosts.

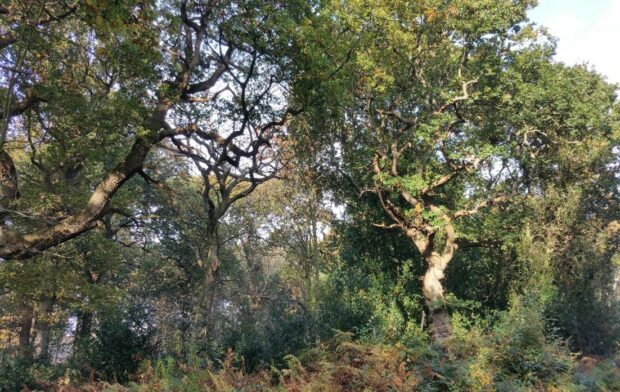

Consider allocating areas of your woodland as minimum intervention sites, to allow for natural processes to take place, providing grazing/browsing is kept to a low level. High forest, areas of lapsed coppice, neglected direct planting or regeneration are potential sites to consider, especially where access and adequate infrastructure are an issue, or the area is susceptible to water logging. Such sites with their closed canopy and dense native understorey, shady, dappled interior, native trees and shrubs of different ages and heights, broken stems and fallen limbs, shimmering with humidity are humming with midges, flies and moths - the perfect bat buffet especially for our woodland specialist bats like the barbastelle, Bechstein’s bat and brown long-eared bat.

Scrubby vegetation, thorny, messy and dense supports a diverse range of insects and will provide bat food and key wildlife corridors especially if located within open glades, clearings and along woodland edges.

Improve the boundary along woodland edges, rides, glades and open spaces by encouraging a succession of vegetation, from scrub, tall grasses, herbaceous plants to short grasses, with overhanging vegetation and branches, scallop edges to provide shelter and pinch points across rides to allow for movement across the woodland. This will encourage a variety of insects along edge habitats, perfect hunting grounds for our more generalist bat species like the common and soprano pipistrelles.

Ensure woodlands are connected and not fragmented. We know hedgerows are good wildlife corridors, but they can also provide a source of food and roosting habitats. Work with landowners outside your woodland to ensure hedgerows are retained and managed appropriately. Ideally, we want a dense structure and hedgerow trees to be retained. Reducing the frequency of hedgerow trimming and rethinking the timing of this kind of management has been found to increase insect abundance and create a varied and dense structure. Avoiding cutting in the autumn so berries and insect larvae remain readily available would also benefit bats, birds and other wildlife.

As Oliver Rackham, leading ecologist of British Woodlands, once said “our woods are a living, breathing part of our heritage and therefore it is our responsibility to protect them. In owning a wood, you are playing a part in ensuring its conservation.” A woodland managed appropriately can support an impressive range of wildlife, including our only true flying mammal, our bats.

Bat Conservation Trust is a charity solely devoted to the conservation of bats and the landscapes on which they rely. They provide training courses for people working with trees to help them understanding how bats use trees, the best time of year for tree works and the legal responsibilities around these protected species. Book now for:

European Protected Species for Foresters, Tuesday, 10 September 2024 -Lyme Park & Goyte Forest, Stockport, SK12 2NR

European Protected Species for Forester, Wednesday, 11 September 2024 - Near Chadlington, Chipping Norton.

You could also participate in their Sunset Sunrise Survey between now and October.

1 comment

Comment by sam d posted on

In Lady Park Wood (non-intervention site) deer were totally excluded and the site was good for Barbastelle. I think fencing or deer management would be useful (esp. in non-intervention areas) to help understories flourish?