Chris Watson, Woodland Resilience Advisor at the Forestry Commission, invites Steph Bale, Senior Policy Advisor for Commercial Forestry at Defra, to discuss the differences between hardwood and softwood in relation to timber, and why it matters.

Chris Watson, Woodland Resilience Advisor at the Forestry Commission, invites Steph Bale, Senior Policy Advisor for Commercial Forestry at Defra, to discuss the differences between hardwood and softwood in relation to timber, and why it matters.

Visit any woodland in England and you could find yourself amongst a wide variety of trees, from leafy, deciduous, broadleaved trees like oak, beech and birch, to straight, evergreen conifers like pine, spruce and fir. When we grow these trees for timber, we use the terms hardwoods and softwoods to describe these two main groups.

What are hardwoods and softwoods?

Despite the terms we use, hardwoods aren’t always harder than softwoods. Balsa, a familiar wood to many and renowned for being soft and light, is actually a hardwood. The difference between the groups is biological, not simply how ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ they are.

Hardwood from broadleaf trees

Hardwoods found in the UK and Europe typically come from broadleaves that usually lose their leaves in autumn and winter. They are botanically classified as Angiosperms (flowering plants with seeds typically contained within a fruit).

Softwood from coniferous trees

Softwoods come from conifers, which usually keep their needles all year round, and are classed as gymnosperms (where tree seeds are not contained within a fruit).

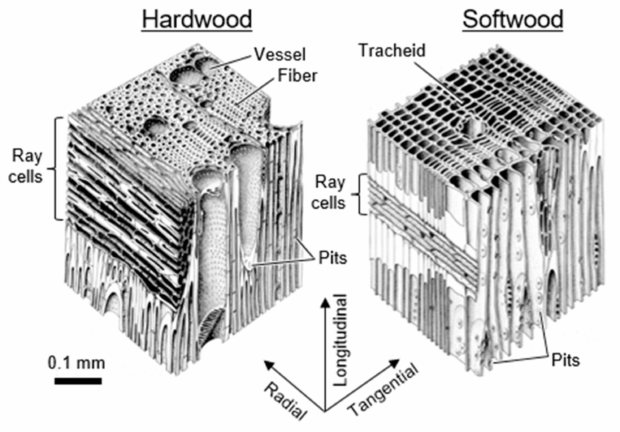

At the microscopic level, hardwoods and softwoods are fundamentally different because of their cell structure. This influences their physical properties and ultimately how we use them.

Different structures that differentiate hardwood from softwood

Hardwoods have a more complex cell structure which often gives them a very distinctive grain and texture when turned into timber. This complexity generally makes hardwoods denser, harder and more durable, which is why they often get used for more long-lasting products such as flooring and furniture.

Softwoods have a simpler cell structure and a good strength to weight ratio. This simple cell structure makes softwoods generally lighter, more uniform and easier to saw and process which makes them well suited to construction like structural beams, sawn products like fencing rails and pulp for paper production.

Wood that goes against the grain

There are of course exceptions to these general descriptions, and some end uses like flooring or blockboard can use softwood, hardwood, or a combination of the two. However, these differences help explain why hardwoods tend to get used for higher value products which recognise their character and durability, while softwoods are better suited to larger, more industrial markets where uniformity and ease of processing are valued.

Seeing the wood for the trees

What makes a good timber tree? Trees vary enormously in their structural properties, growth rate and form. This variation can be helpful, making species suitable for different uses. For example, oak and larch are naturally durable and resist decay – great for use outside, while spruce is less durable but strong and light – great for structural construction.

Regardless of its end use, good timber trees share some important traits; they should grow tall and straight with a single, cylindrical stem and few branches. This helps produce knot-free boards and improves processing efficiency. Good form is essential for both hardwoods and softwoods, as it reduces waste and increases value.

Growth rate is another key factor. Faster-growing trees reach harvestable size sooner, providing quicker returns on investment for landowners, while also sequestering carbon faster. A fast growth rate is also helpful when establishing trees in new woodlands or after harvesting, as it means the trees require less maintenance and therefore reduced establishment costs.

Growing hardwoods and softwoods as timber

Growing broadleaved trees for timber requires more intensive and skilled management than softwoods. Unlike conifers, which often grow tall and straight with little intervention, broadleaves are prone to developing multiple stems, heavy branching and develop an irregular form if left unmanaged. This can be exacerbated by pressures from grey squirrels and browsing animals.

Hardwood timber

To produce high-quality timber, broadleaved trees need early and ongoing attention, including formative pruning, regular thinning and careful spacing to encourage straight, single-stem growth to limit knots or defects in the wood. Without this level of care, many broadleaf species will grow into shapes only suitable for lower-value wood products such as firewood rather than valuable sawlogs.

One distinct advantage hardwood trees have is their ability to coppice (regrow from the stump). Most native hardwoods, for example oak, hazel and alder can be coppiced. Traditionally, this trait has been used to deliver regular crops of uniform, small diameter wood product useful for a whole range of traditional crafts, many of which still have good markets today.

Producing hardwood timber takes longer and requires greater investment, planning and patience than is the case for softwoods. However, the rewards can be incredibly satisfying and fruitful as hardwood is often considered a beautiful, durable timber with strong market appeal. The added bonus is, that you’ll be managing some of our most valued native woodlands. Growing quality hardwood timber really is a gift to future generations.

Softwood timber

Softwoods are generally easier and more predictable to manage for timber production, making them well-suited to commercial forestry. Many conifer species, such as Sitka spruce, Douglas fir, and Scots pine have a natural tendency to grow tall, straight and with a single main stem, reducing the need for pruning. When planted at high density, their lower branches often self-prune (die off naturally), helping to produce clean, knot-free logs.

Softwoods also grow more quickly and respond well to standardised management practices, such as systematic thinning and clear-felling, which fit efficiently into mechanised operations. This makes them ideal for producing uniform timber on shorter rotations, with lower labour input and quicker returns, especially on upland or poorer-quality sites. Historically, this ability to thrive on poorer sites has seen the establishment of large softwood plantations on otherwise poor quality, low value agricultural land.

Felled areas of softwoods usually need to be restocked through planting or natural regeneration, which requires longer timeframes to establish and more care to maintain.

What does this mean in practice?

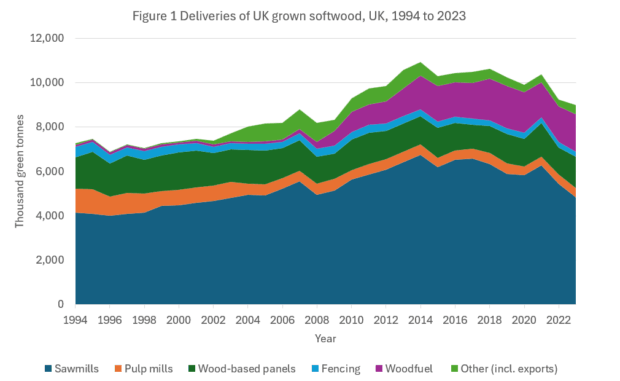

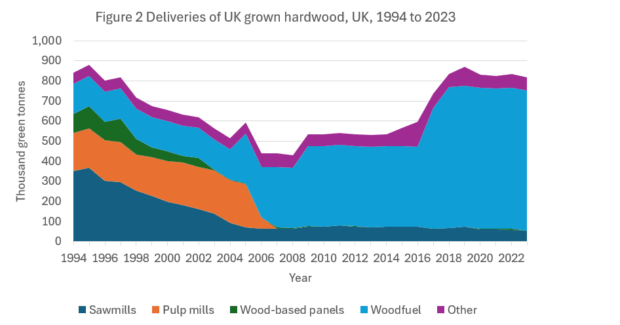

In the UK, we have a significant forest resource which produces around 20% of the timber and wood products we use. However, 92% of this harvested wood is softwood,1 despite softwoods making up only 48% of the total forest area.2 In England, this difference is even more pronounced, with 23% of woodland area being softwoods but producing 73% of the timber harvested.3

Of the volume harvested, the majority of softwoods are used for sawn timber, wood panels and other products with the potential to lock up stored carbon for a long time after manufacturing, with relatively small proportions ending up as woodfuel. In comparison, most of the hardwood volume harvested in the UK was used for woodfuel.

There are two crucial points to pull from these statistics:

Firstly, softwoods are the dominant timber used by the processing sector and will likely continue to be. It is important that as part of our efforts to increase woodland area, we increase rates of conifer planting to help to meet this demand. We have an aim to increase conifer planting to 30% of total planting.

For landowners, softwoods provide a great opportunity to generate revenue from tree planting with little doubt over future demand. While imports will continue to be an important part of our timber industry, there is a once in a generation opportunity for our domestic timber sector to grow and innovate.

Secondly, our hardwoods represent a significant opportunity. In England, 77% of our woodland area is broadleaved4 with very low harvesting rates compared to the potential sustainable harvest.5 The proportion of this resource that could be brought to market as timber (instead of woodfuel) could be greatly increased through increasing the management of our broadleaved woodlands.

The need for quality in hardwoods means that we need to take care to consider future management requirements where we create new broadleaved woodlands. Species choice, planting pattern and careful planning for the protection and future resilience and management of new broadleaved woodlands are critical if we want to produce timber in the future.

Weighing up hardwood and softwood timber

Hardwoods and softwoods each have their uses, and both are needed if we are to support a low carbon, green economy. In the next blog we will look at what products our woodlands can produce, how you can identify what wood products you may have in your woodland, and how they could be utilised.

Find out more about the financial and environmental benefits of home-grown timber.

1 comment

Comment by Ian Briscoe posted on

Great Blog Chris, really clear and easy to follow with some really interesting stats!